We're back in Italy at the 29th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. One of the sections I'm curious about is Beautiful Youth: Renato Castellani. The Italian film director and screenwriter made that wonderful young love trilogy of Neorealism: Sotto il sole di Roma/Under the Sun of Rome (1948), È primavera.../Springtime in Italy (1950) and Due soldi di speranza/Two Cents Worth of Hope (1952). In the latter, screened today, the female lead is played by little-known Maria Fiore (1935–2004). The Italian film actress appeared in 50 films between 1952 and 1999. Throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s, she played in many romantic comedies and musicals, often set in Naples.

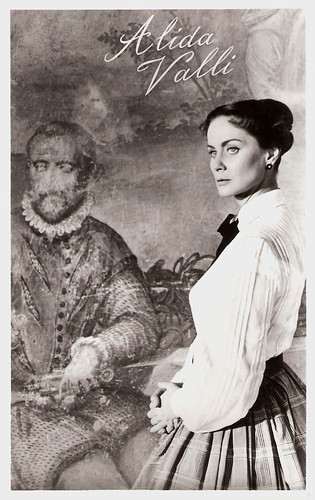

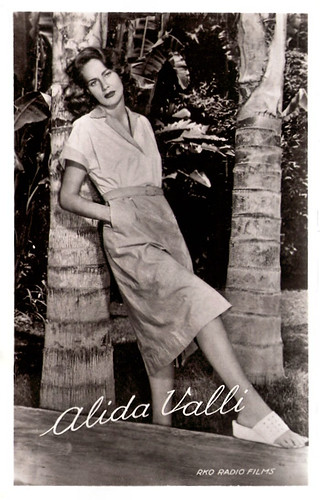

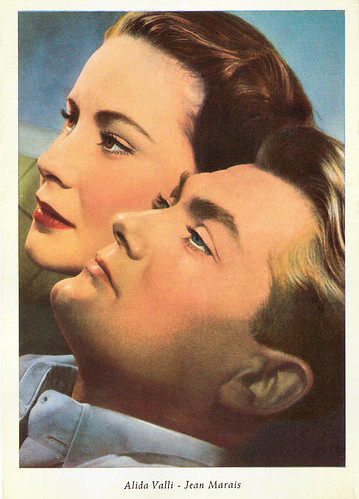

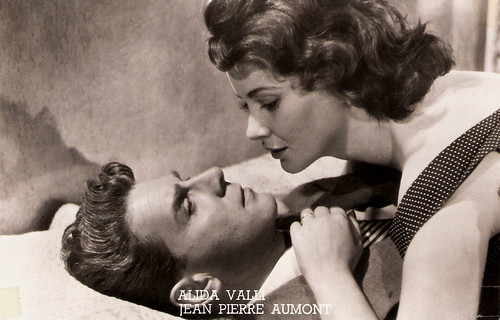

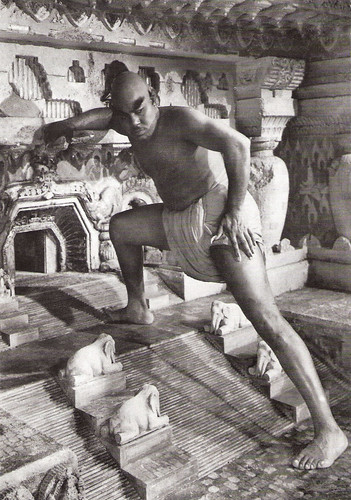

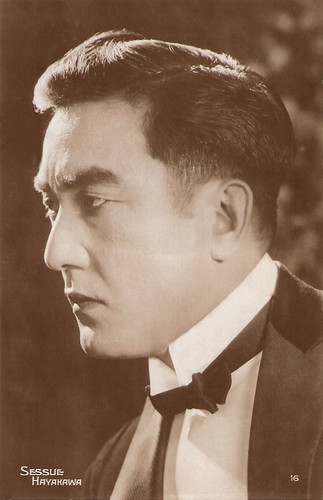

Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., Firenze, no 2917. Photo: Cines. Publicity still for Tempi nostri - Zibaldone n. 2/A Slice of Life (Alessandro Blasetti, Paul Paviot, 1954).

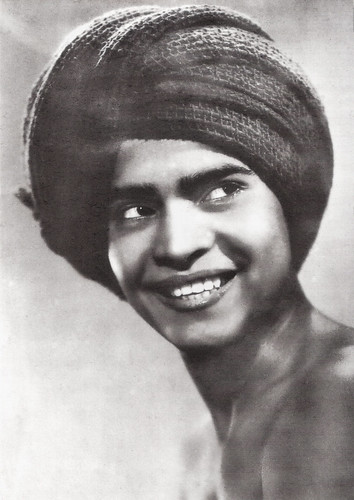

Maria Fiore was born Jolanda Di Fiore in Rome in 1935. She made an impressive film debut at 17 in the neo-realistic masterpiece Due soldi di speranza/Two Cents Worth of Hope (Renato Castellani, 1952), the third in director Castellani's young love trilogy. The story concerns the romance between the strong-willed and free-spirited Carmela (Fiore) and Antonio (Vincenzo Musolino). At the 1952 Cannes Film Festival, the film shared the Grand Prix with Orson Welles’ Othello (1952).

Hal Erickson at AllMovie: “The ardor is one-sided at first, but Carmela is a determined young woman, willing to scale and conquer any obstacle in pursuing her heart's desire. Once he's ‘hooked,’ Antonio scurries from job to job to prove his financial viability. Faced with their parents's hostility, Carmela and Antonio symbolically shed themselves of all responsibilities to others in a climactic act of stark-naked bravado.”

Fiore then co-starred with Sophia Loren in the drama-comedy La domenica della buona gente/Good Folk’s Sunday (Anton Giulio Majano, 1953) and played the title role opposite Henri Vidal in Scampolo 53 (Giorgio Bianchi, 1953), one of the many film versions of the Dario Niccodemi play.

The next year, she played an important supporting part in Carosello napoletano/Neapolitan Carousel (Ettore Giannini, 1954), the first major Italian musical of the post-war era. Léonide Massine starred as Antonio Petito, a notable Pulcinella performer, and an important figure of Neapolitan theatre in the 19th century. The film was entered into the 1954 Cannes Film Festival.

During the next decade, Fiore starred in many romantic comedies and musicals, often set in Naples. Titles include Graziella (Giorgio Bianchi, 1955) with Jean-Pierre Mocky, I pappagalli/The Parrots (Bruno Paolinelli, 1955) starring Aldo Fabrizi and Alberto Sordi, Serenata a Maria/Serenade for Maria (Luigi Capuano, 1957), and Malafemmena (Armando Fizzarotti, 1957). These films were popular in Italy, but less known abroad. Later, when the Peplum genre became popular, she appeared credited as Joan Simons in epics like Ercole l'invincibile/Hercules the Invincible (Alvaro Mancori, 1964).

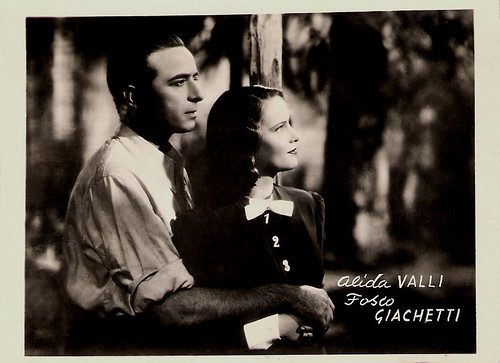

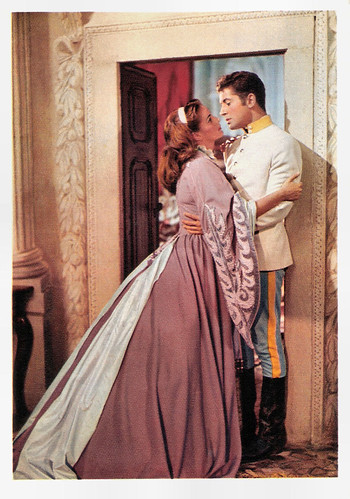

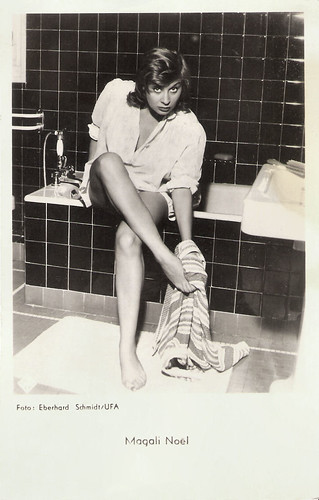

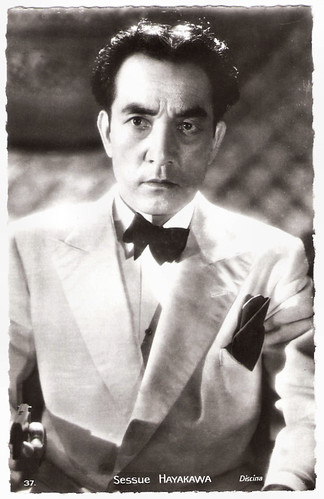

Italian postcard by Levibrom, Milano.

Maria Fiore disappeared from the big screen in the mid-1960s to concentrate on the dubbing firm she had set up.

She returned to popular success through hit TV mini-series such as Joe Petrosino (Daniele D'Anza, 1972) with Adolfo Celi, Accadde a Lisbona/It happened in Lisbon (Daniele D'Anza, 1974) with Paolo Stoppa, L'ultimo aereo per Venezia/The last plane to Venice (Daniele D'Anza, 1977) with Massimo Girotti, Quei 36 gradini/Those 36 steps (Luigi Perelli, 1984) with Gérard Blain, Little Roma (Francesco Massaro, 1988) and Pronto Soccorso/First Aid (Francesco Massaro, 1990-1992).

In the cinema she could be seen in the anthology film Se permettete parliamo di donne/Let's Talk About Women (Ettore Scola, 1964) with Vittorio Gassman, and the crime film L'onorata famiglia - Uccidere è cosa nostra/The Big Family (Tonino Ricci, 1973).

In 1975, Fiore played a supporting role in the Poliziotteschi film Il giustiziere sfida la città/Syndicate Sadists (Umberto Lenzi, 1975), starring Joseph Cotten and Tomas Milian. This film, also known as Rambo's Revenge and One Just Man, was one of director Lenzi's many efforts in the crime thriller genre. Tomas Milián plays Rambo, an ex-cop who seeks revenge against two powerful crime families who were responsible for the murder of his friend. The film predates Ted Kotcheff's First Blood (1982), which introduced audiences to the John Rambo of author David Morrell by seven years. Milian read Morrell's novel while flying from the U.S. to Rome. Loving the story he tried to talk some Italian producers into making a film out of it, with him starring as John Rambo. Nothing came of this, but he was allowed to use the Rambo moniker in the next Poliziottesco he starred in.

Fiore’s last film was E insieme vivremo tutte le stagioni/And Together We Will Live All Seasons (Gianni Minello, 1999), starring Franco Citti. In 2004, Maria Fiore died in Rome of lung cancer. She was 68.

Final scene of Due soldi di speranza/Two Cents Worth of Hope (1952). Source: Ugo Tramontano (YouTube).

Sources: Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Guy Bellinger (IMDb), Wikipedia (English and Italian), and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 19 March 2024.

Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., Firenze, no 2917. Photo: Cines. Publicity still for Tempi nostri - Zibaldone n. 2/A Slice of Life (Alessandro Blasetti, Paul Paviot, 1954).

A determined young woman

Maria Fiore was born Jolanda Di Fiore in Rome in 1935. She made an impressive film debut at 17 in the neo-realistic masterpiece Due soldi di speranza/Two Cents Worth of Hope (Renato Castellani, 1952), the third in director Castellani's young love trilogy. The story concerns the romance between the strong-willed and free-spirited Carmela (Fiore) and Antonio (Vincenzo Musolino). At the 1952 Cannes Film Festival, the film shared the Grand Prix with Orson Welles’ Othello (1952).

Hal Erickson at AllMovie: “The ardor is one-sided at first, but Carmela is a determined young woman, willing to scale and conquer any obstacle in pursuing her heart's desire. Once he's ‘hooked,’ Antonio scurries from job to job to prove his financial viability. Faced with their parents's hostility, Carmela and Antonio symbolically shed themselves of all responsibilities to others in a climactic act of stark-naked bravado.”

Fiore then co-starred with Sophia Loren in the drama-comedy La domenica della buona gente/Good Folk’s Sunday (Anton Giulio Majano, 1953) and played the title role opposite Henri Vidal in Scampolo 53 (Giorgio Bianchi, 1953), one of the many film versions of the Dario Niccodemi play.

The next year, she played an important supporting part in Carosello napoletano/Neapolitan Carousel (Ettore Giannini, 1954), the first major Italian musical of the post-war era. Léonide Massine starred as Antonio Petito, a notable Pulcinella performer, and an important figure of Neapolitan theatre in the 19th century. The film was entered into the 1954 Cannes Film Festival.

During the next decade, Fiore starred in many romantic comedies and musicals, often set in Naples. Titles include Graziella (Giorgio Bianchi, 1955) with Jean-Pierre Mocky, I pappagalli/The Parrots (Bruno Paolinelli, 1955) starring Aldo Fabrizi and Alberto Sordi, Serenata a Maria/Serenade for Maria (Luigi Capuano, 1957), and Malafemmena (Armando Fizzarotti, 1957). These films were popular in Italy, but less known abroad. Later, when the Peplum genre became popular, she appeared credited as Joan Simons in epics like Ercole l'invincibile/Hercules the Invincible (Alvaro Mancori, 1964).

Italian postcard by Levibrom, Milano.

Rambo's revenge

Maria Fiore disappeared from the big screen in the mid-1960s to concentrate on the dubbing firm she had set up.

She returned to popular success through hit TV mini-series such as Joe Petrosino (Daniele D'Anza, 1972) with Adolfo Celi, Accadde a Lisbona/It happened in Lisbon (Daniele D'Anza, 1974) with Paolo Stoppa, L'ultimo aereo per Venezia/The last plane to Venice (Daniele D'Anza, 1977) with Massimo Girotti, Quei 36 gradini/Those 36 steps (Luigi Perelli, 1984) with Gérard Blain, Little Roma (Francesco Massaro, 1988) and Pronto Soccorso/First Aid (Francesco Massaro, 1990-1992).

In the cinema she could be seen in the anthology film Se permettete parliamo di donne/Let's Talk About Women (Ettore Scola, 1964) with Vittorio Gassman, and the crime film L'onorata famiglia - Uccidere è cosa nostra/The Big Family (Tonino Ricci, 1973).

In 1975, Fiore played a supporting role in the Poliziotteschi film Il giustiziere sfida la città/Syndicate Sadists (Umberto Lenzi, 1975), starring Joseph Cotten and Tomas Milian. This film, also known as Rambo's Revenge and One Just Man, was one of director Lenzi's many efforts in the crime thriller genre. Tomas Milián plays Rambo, an ex-cop who seeks revenge against two powerful crime families who were responsible for the murder of his friend. The film predates Ted Kotcheff's First Blood (1982), which introduced audiences to the John Rambo of author David Morrell by seven years. Milian read Morrell's novel while flying from the U.S. to Rome. Loving the story he tried to talk some Italian producers into making a film out of it, with him starring as John Rambo. Nothing came of this, but he was allowed to use the Rambo moniker in the next Poliziottesco he starred in.

Fiore’s last film was E insieme vivremo tutte le stagioni/And Together We Will Live All Seasons (Gianni Minello, 1999), starring Franco Citti. In 2004, Maria Fiore died in Rome of lung cancer. She was 68.

Final scene of Due soldi di speranza/Two Cents Worth of Hope (1952). Source: Ugo Tramontano (YouTube).

Sources: Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Guy Bellinger (IMDb), Wikipedia (English and Italian), and IMDb.

This post was last updated on 19 March 2024.