Great French film director Abel Gance (1889-1981) was also a producer, writer and actor. He is best known for his three silent masterpieces: J'accuse/I Accuse (1919), La Roue/The Wheel (1923), and the monumental Napoléon (1927).

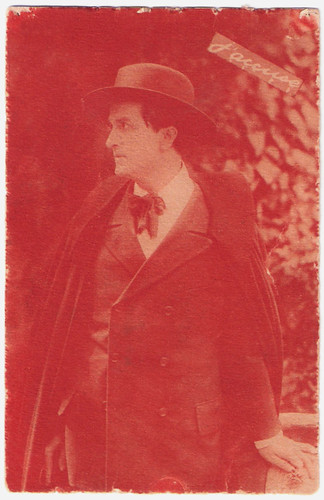

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 473. Photo: publicity still for Napoléon (1927, Abel Gance), with Gance himself as Saint Just.

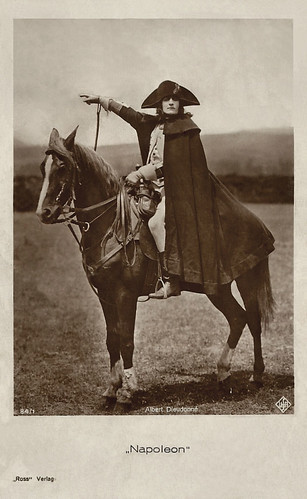

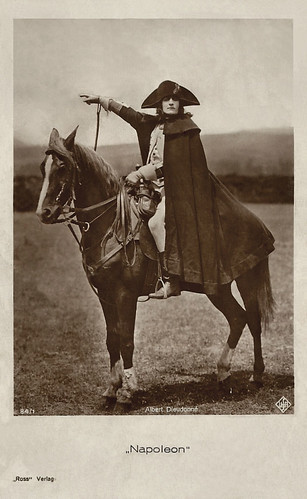

Albert Dieudonné in Napoléon (1927). German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 84/1. Photo: Ufa.

Love Of Literature And Art

Abel Gance was born in Paris in 1889. He was the illegitimate son of a wealthy doctor, Abel Flamant, and a working class mother, Françoise Péréthon (or Perthon). Initially taking his mother's name, he was brought up until the age of eight by his maternal grandparents in the coal mining town of Commentry in central France. He then returned to Paris to rejoin his mother who had by then married Adolphe Gance, a chauffeur and mechanic, whose name Abel then adopted. Although he later fabricated the history of a brilliant school career and middle-class background, Gance left school at the age of 14, and the love of literature and art which sustained him throughout his life was in part the result of self-education. He started working as a clerk in a solicitor's office, but after a couple of years he turned to acting in the theatre. When he was 18, he was given a season's contract at the Théâtre Royal du Parc in Brussels, where he developed a friendship with the actor Victor Francen. While in Brussels, Gance wrote his first film scenarios, which he sold to director Léonce Perret. Back in Paris in 1909, he acted in his first film, Molière (1909, Léonce Perret). At that stage he regarded the cinema as ‘infantile and stupid’ and was only drawn into film jobs by his poverty, but he nevertheless continued to write scenarios, and often sold them to Gaumont. During this period he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, often fatal at that time, but after a period of retreat in Vittel, he overcame the disease. With some friends he established a production company, Le Film Français, and began directing his own films in 1911. His first effort was La Digue/The Dam (1911), a historical film which featured the first screen appearance of Pierre Renoir. The film was never released. Gance tried to maintain a connection with the theatre and he finished writing a monumental tragedy entitled Victoire de Samothrace, in which he hoped that Sarah Bernhardt would star. Its five-hour length, and Gance's refusal to cut it, proved to be a stumbling block. With the outbreak of World War I, Gance was rejected from the army on medical grounds and in 1915 he started writing and directing for a new film company, Film d'Art. He soon caused controversy with La Folie du docteur Tube/The Madness of Dr. Tube (1915), in which a scientist (Albert Dieudonné) takes a white powder, and then hallucinates. Gance and his cameraman Léonce-Henry Burel created the arresting hallucinations with distorting mirrors. According to Wikipedia, the producers were outraged and refused to show the film. A print of the film survives and Gance continued working for Film d'Art until 1918, making over a dozen commercially successful films. His experiments included tracking shots, extreme close-ups, low-angle shots, and split-screen images. His subjects moved steadily away from simple action films towards psychological melodramas, such as Mater dolorosa/The Torture of Silence (1917) starring Emmy Lynn as a neglected wife who has an affair with her husband's brother. The film was a great commercial success, and it was followed by La Dixième Symphonie/The Tenth Symphony (1918), another marital drama featuring Emmy Lynn. Here Gance's mastery of lighting, composition and editing was accompanied by a range of literary and artistic references which some critics found pretentious and alienating. In 1917, Gance was at last drafted into the Army, in its Service Cinématographique. It deepened his preoccupation with the impact of the war and the depression which was caused by the deaths of many of his friends. He was discharged shortly after due to mustard gas poisoning.

Romuald Joubé and Maryse Dauvray. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

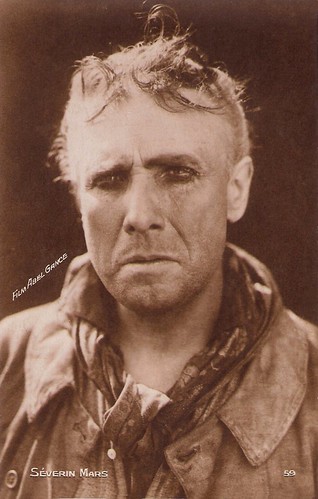

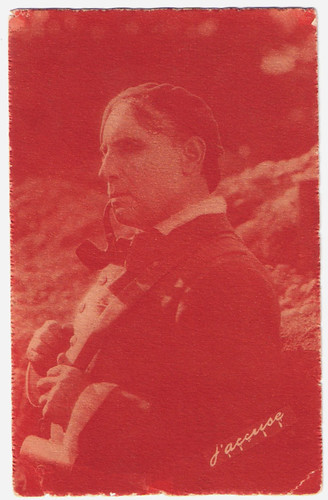

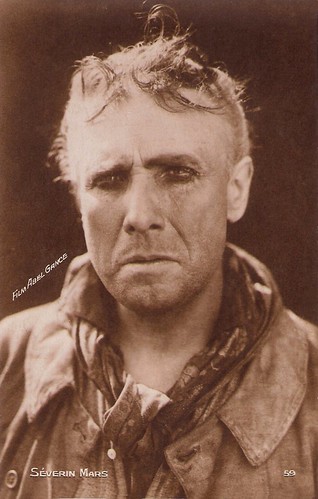

Séverin-Mars. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

Romuald Joubé. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

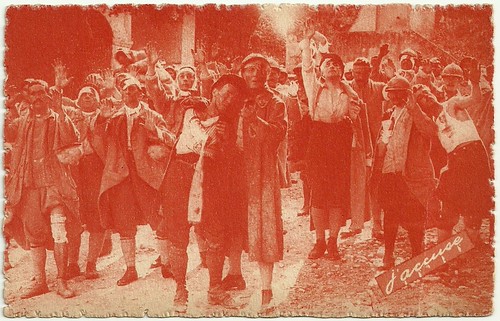

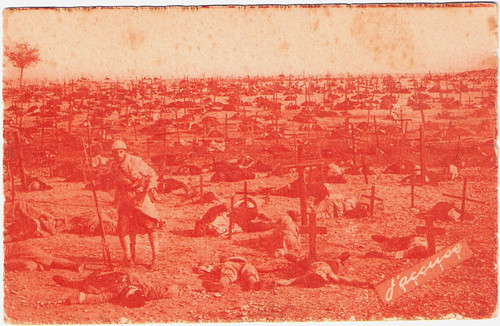

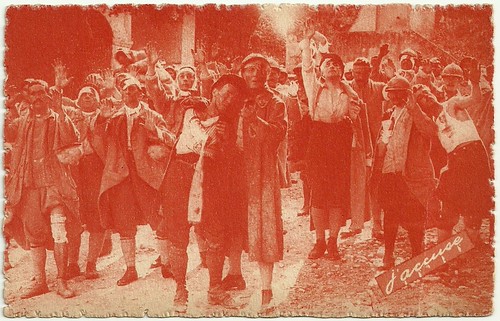

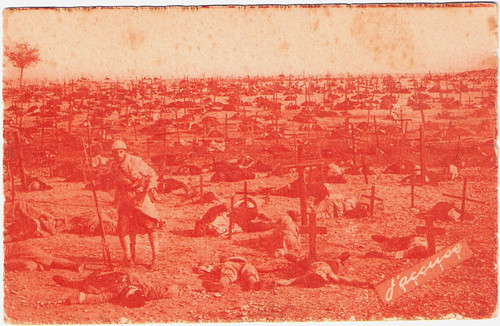

French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

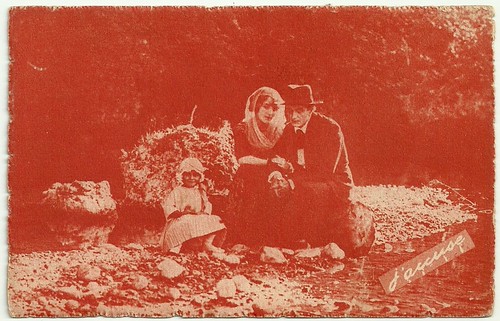

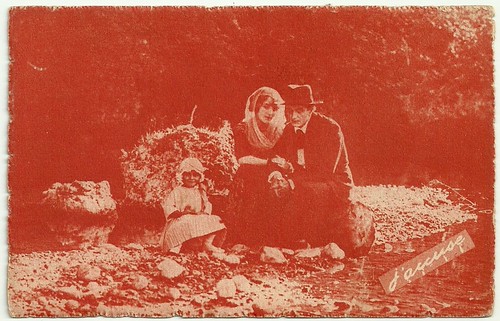

Edith (Marise Dauvray), Jean Diaz (Romuald Joubé) and little Angele (Angèle Guys) towards the end of J'accuse. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

The Horror and Absurdity of War

When Abel Gance parted company with Film d'Art over a shortage of funds, Charles Pathé stepped in, and produced his next film, J'accuse/I Accuse (1919) with Romuald Joubé and Séverin-Mars. Gance juxtaposed a romantic drama with the background of the waste and suffering of World War I. He re-enlisted himself into the Service Cinématographique in order to be able to film some scenes on a real battlefield at the front. The film's powerful depiction of wartime horrors, and particularly its climactic sequence of the ‘return of the dead’, made it an international success, and confirmed Gance as one of the most important directors in Europe. James Travers at Films de France: “Abel Gance’s powerful anti-war film still has the power to move and shock. Through the intimate microcosm of two soldiers united on the battlefield, Gance shows the horror and absurdity of war for all its worth. The question he poses is: if two rivals in love can settle their differences in peace, why cannot political leaders?“ In 1920 he developed his next project, La Roue/The Wheel (1923), while recuperating in Nice from Spanish flu, and its progress was deeply affected by the knowledge that his companion Ida Danis was dying of tuberculosis. His leading man and friend Séverin-Mars was also seriously ill - and died soon after completion of the film. Nevertheless Gance brought an unprecedented level of energy and imagination to the technical realisation of his film. The story is about a father (Séverin-Mars) and his son (Gabriel de Gravone) who both fall for the lovely adopted Norma (Ivy Close). This love triangle is set firstly against the dark and grimy background of locomotives and railway yards, and then among the snow-covered landscapes of the Alps. Gance employed elaborate editing techniques and innovative use of rapid cutting which made the film highly influential among other contemporary directors. The film cost 3 million French francs and took five years to complete, an extraordinarily risky venture at the time, and a major cause of anxiety for the film’s production company, Pathé. The finished film was originally in 32 reels and ran for nearly 9 hours, but it was subsequently edited down for distribution and these shorter versions have survived. Gance had a brief change of pace with Au secours/Help! (1924), a short haunted house comedy with Max Linder, which he filmed in only three days. Then he embarked on his greatest project, a six-part life of Napoléon Bonaparte. Only the first part was completed, tracing Bonaparte's early life, through the Revolution, and up to the invasion of Italy, but even this occupied a vast canvas with meticulously recreated historical scenes and scores of characters. Napoléon (1927), featuring Albert Dieudonné, is full of experimental techniques, combining rapid cutting, hand-held cameras, superimposition of images, and, most famously, his wide-screen sequences. Gance achieved them with a system he called Polyvision, by using triple cameras (and projectors) to create a spectacular panoramic effect. In the climactic finale, he created a widescreen image of a French flag with the outer two film panels tinted blue and red. The original version of Napoléon ran for 6 hours. A shortened version received a triumphant première at the Paris Opéra in April 1927 before a distinguished audience that included the future General de Gaulle. The length was reduced still further for French and European distribution, and it became even shorter when it was shown in America. This was not the end of the film's career however. Gance re-used material from it in later films, and the triumphant restoration of the silent film in the 1980’s confirmed it as his most famous work. James Travers: “Napoléon is both a stunningly visual work of cinema and a poetically beautiful telling of the life of France’s most famous general.”

Séverin-Mars. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 59. Photo: Film Abel Gance. Publicity still for La Roue/The Wheel (1923).

Gabriel de Gravone. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 224. Photo: G.L. Manuel Frères.

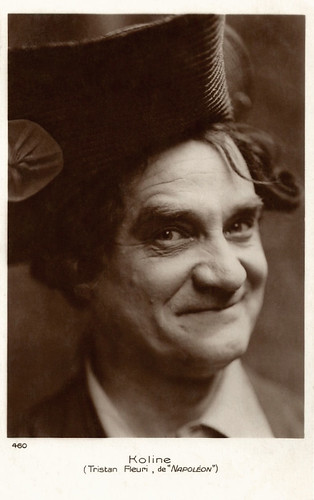

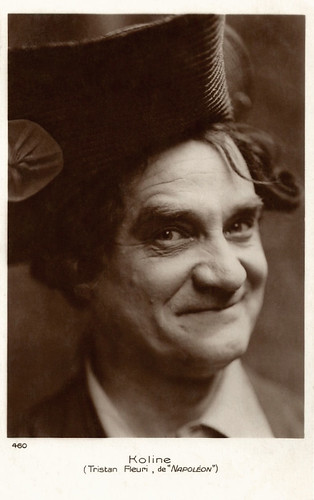

Nicolas Koline as Tristan Fleuri in Napoléon. French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 460. Publicity still for Napoléon (1927).

A Critical And Commercial Disaster

Abel Gance embraced the arrival of sound with enthusiasm and his first production was La Fin du monde/End of the World (1931) starring Victor Francen and Gance himself. This was an expensive science-fiction film about a comet hurling toward Earth on a collision course and the different reactions to people on the impending disaster. Gance had edited it to a running time of just over three hours. When the backers felt that the film was becoming far too long, they took production control away from Gance and cut the film to a shorter length. The result was a critical and commercial disaster. Thereafter the creative independence which Gance had enjoyed in the previous decade was seriously curtailed. He continued to be a busy film-maker throughout the 1930’s, but he characterised most of the films made during this period as ones that he did ‘not in order to live, but in order not to die’. In 1932 he tried to demonstrate his credentials as a reliable and efficient director by filming a remake of Mater dolorosa which he completed within 18 days and within budget. Among the other 'commercial' works that followed were Lucrèce Borgia/Lucretia Borgia (1935) with Edwige Feuillère, and Un Grand Amour de Beethoven/Beethoven's Great Love (1937), with Harry Baur as the composer. One of the more personal projects that he was able to undertake was a new version of J'accuse/I Accuse (1939) starring Victor Francen, not so much a remake of his 1919 film as a continuation of it. Gance conceived it as a warning against the new war that he saw impending. In the upheaval following the German invasion of France in the summer of 1940, Gance went to the Free Zone in the south. He arranged a contract to make a film, Vénus aveugle/Blind Venus (1941) featuring Viviane Romance, at the Victorine studios in Nice. He saw it as an allegory of the current state of France and a message of hope directed to the ordinary French people in their time of misfortune. At this period Gance was among those who saw Philippe Pétain as the means of the country's salvation, and in September 1941 Vénus aveugle had its first screening in Vichy, preceded by a speech in which Gance paid tribute to Pétain. On the other hand, even before its première the film became the object of an attack from the collaborationist and anti-Semitic newspaper Aujourd'hui, which insinuated that the freedoms of film-making in the unoccupied zone in the south of France were being exploited by Jews: the producer Jean-Jacques Mecatti, Viviane Romance, and Gance himself were singled out for derisive references to their Jewish connections. After completing one more film, Le Capitaine Fracasse/Captain Fracasse (1943) with Fernand Gravey, Gance went to Spain in August 1943, citing growing hostility from the German authorities in France. He remained there until October 1945. After the war, his difficulties in getting support for his projects increased and he made few films. The historical melodrama La Tour de Nesle/Tower of Nesle (1954) with Silvana Pampanini and Pierre Brasseur was his first film in colour. It provoked some revival of interest in his work, and François Truffaut named Gance a neglected auteur of genius. Gance returned to Napoleonic spectacle with Austerlitz/The Battle of Austerlitz (1960) starring Pierre Mondy as Napoleon. He made a further historical pageant in Cyrano et d'Artagnan/Cyrano and d'Artagnan (1963) starring José Ferrer and Jean-Pierre Cassel, and then moved into television for his final works, also on historical subjects. Throughout his life, Gance kept returning to Napoléon, often editing his own footage into shorter versions, adding a soundtrack, sometimes filming new material, and as a result the original 1927 film was lost from view for decades. After various attempts at reconstruction, the dedicated work of the film historian Kevin Brownlow produced a five-hour version of the film, still incomplete but fuller than anyone had seen since the 1920’s. This version was presented at the Telluride Film Festival in August 1979, with the frail 89-year old director in attendance. The occasion brought a belated triumph to Gance's career, and subsequent performances and further restoration made his name known to a worldwide audience. Abel Gance married three times: in 1912 to Mathilde Thizeau; in 1922 to Marguerite Danis (sister of Ida); in 1933 to Marie-Odette Vérité (Sylvie Grenade), who died in 1978. Gance died of tuberculosis in Paris in 1981 at the age of 92. He still had plans of making an epic film about Christopher Columbus.

Trailer for Napoleon (1927), presented by San Francisco Silent Film Festival. Source: SFSilent Film (YouTube).

Sources: James Travers (Films de France), Wikipedia, AllMovie and IMDb.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 473. Photo: publicity still for Napoléon (1927, Abel Gance), with Gance himself as Saint Just.

Albert Dieudonné in Napoléon (1927). German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 84/1. Photo: Ufa.

Love Of Literature And Art

Abel Gance was born in Paris in 1889. He was the illegitimate son of a wealthy doctor, Abel Flamant, and a working class mother, Françoise Péréthon (or Perthon). Initially taking his mother's name, he was brought up until the age of eight by his maternal grandparents in the coal mining town of Commentry in central France. He then returned to Paris to rejoin his mother who had by then married Adolphe Gance, a chauffeur and mechanic, whose name Abel then adopted. Although he later fabricated the history of a brilliant school career and middle-class background, Gance left school at the age of 14, and the love of literature and art which sustained him throughout his life was in part the result of self-education. He started working as a clerk in a solicitor's office, but after a couple of years he turned to acting in the theatre. When he was 18, he was given a season's contract at the Théâtre Royal du Parc in Brussels, where he developed a friendship with the actor Victor Francen. While in Brussels, Gance wrote his first film scenarios, which he sold to director Léonce Perret. Back in Paris in 1909, he acted in his first film, Molière (1909, Léonce Perret). At that stage he regarded the cinema as ‘infantile and stupid’ and was only drawn into film jobs by his poverty, but he nevertheless continued to write scenarios, and often sold them to Gaumont. During this period he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, often fatal at that time, but after a period of retreat in Vittel, he overcame the disease. With some friends he established a production company, Le Film Français, and began directing his own films in 1911. His first effort was La Digue/The Dam (1911), a historical film which featured the first screen appearance of Pierre Renoir. The film was never released. Gance tried to maintain a connection with the theatre and he finished writing a monumental tragedy entitled Victoire de Samothrace, in which he hoped that Sarah Bernhardt would star. Its five-hour length, and Gance's refusal to cut it, proved to be a stumbling block. With the outbreak of World War I, Gance was rejected from the army on medical grounds and in 1915 he started writing and directing for a new film company, Film d'Art. He soon caused controversy with La Folie du docteur Tube/The Madness of Dr. Tube (1915), in which a scientist (Albert Dieudonné) takes a white powder, and then hallucinates. Gance and his cameraman Léonce-Henry Burel created the arresting hallucinations with distorting mirrors. According to Wikipedia, the producers were outraged and refused to show the film. A print of the film survives and Gance continued working for Film d'Art until 1918, making over a dozen commercially successful films. His experiments included tracking shots, extreme close-ups, low-angle shots, and split-screen images. His subjects moved steadily away from simple action films towards psychological melodramas, such as Mater dolorosa/The Torture of Silence (1917) starring Emmy Lynn as a neglected wife who has an affair with her husband's brother. The film was a great commercial success, and it was followed by La Dixième Symphonie/The Tenth Symphony (1918), another marital drama featuring Emmy Lynn. Here Gance's mastery of lighting, composition and editing was accompanied by a range of literary and artistic references which some critics found pretentious and alienating. In 1917, Gance was at last drafted into the Army, in its Service Cinématographique. It deepened his preoccupation with the impact of the war and the depression which was caused by the deaths of many of his friends. He was discharged shortly after due to mustard gas poisoning.

Romuald Joubé and Maryse Dauvray. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

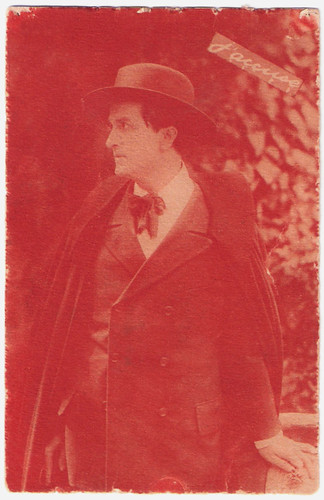

Séverin-Mars. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

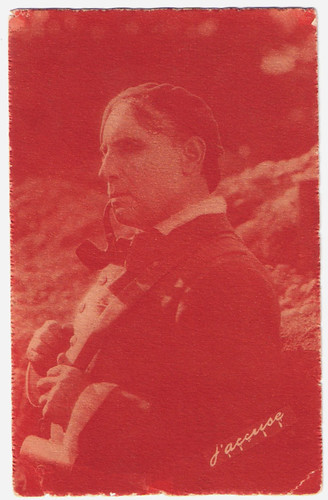

Romuald Joubé. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

Edith (Marise Dauvray), Jean Diaz (Romuald Joubé) and little Angele (Angèle Guys) towards the end of J'accuse. French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

French postcard by Sadag de France, Imp., Paris, no. 109. Photo: publicity still for J'accuse/I Accuse (1919).

The Horror and Absurdity of War

When Abel Gance parted company with Film d'Art over a shortage of funds, Charles Pathé stepped in, and produced his next film, J'accuse/I Accuse (1919) with Romuald Joubé and Séverin-Mars. Gance juxtaposed a romantic drama with the background of the waste and suffering of World War I. He re-enlisted himself into the Service Cinématographique in order to be able to film some scenes on a real battlefield at the front. The film's powerful depiction of wartime horrors, and particularly its climactic sequence of the ‘return of the dead’, made it an international success, and confirmed Gance as one of the most important directors in Europe. James Travers at Films de France: “Abel Gance’s powerful anti-war film still has the power to move and shock. Through the intimate microcosm of two soldiers united on the battlefield, Gance shows the horror and absurdity of war for all its worth. The question he poses is: if two rivals in love can settle their differences in peace, why cannot political leaders?“ In 1920 he developed his next project, La Roue/The Wheel (1923), while recuperating in Nice from Spanish flu, and its progress was deeply affected by the knowledge that his companion Ida Danis was dying of tuberculosis. His leading man and friend Séverin-Mars was also seriously ill - and died soon after completion of the film. Nevertheless Gance brought an unprecedented level of energy and imagination to the technical realisation of his film. The story is about a father (Séverin-Mars) and his son (Gabriel de Gravone) who both fall for the lovely adopted Norma (Ivy Close). This love triangle is set firstly against the dark and grimy background of locomotives and railway yards, and then among the snow-covered landscapes of the Alps. Gance employed elaborate editing techniques and innovative use of rapid cutting which made the film highly influential among other contemporary directors. The film cost 3 million French francs and took five years to complete, an extraordinarily risky venture at the time, and a major cause of anxiety for the film’s production company, Pathé. The finished film was originally in 32 reels and ran for nearly 9 hours, but it was subsequently edited down for distribution and these shorter versions have survived. Gance had a brief change of pace with Au secours/Help! (1924), a short haunted house comedy with Max Linder, which he filmed in only three days. Then he embarked on his greatest project, a six-part life of Napoléon Bonaparte. Only the first part was completed, tracing Bonaparte's early life, through the Revolution, and up to the invasion of Italy, but even this occupied a vast canvas with meticulously recreated historical scenes and scores of characters. Napoléon (1927), featuring Albert Dieudonné, is full of experimental techniques, combining rapid cutting, hand-held cameras, superimposition of images, and, most famously, his wide-screen sequences. Gance achieved them with a system he called Polyvision, by using triple cameras (and projectors) to create a spectacular panoramic effect. In the climactic finale, he created a widescreen image of a French flag with the outer two film panels tinted blue and red. The original version of Napoléon ran for 6 hours. A shortened version received a triumphant première at the Paris Opéra in April 1927 before a distinguished audience that included the future General de Gaulle. The length was reduced still further for French and European distribution, and it became even shorter when it was shown in America. This was not the end of the film's career however. Gance re-used material from it in later films, and the triumphant restoration of the silent film in the 1980’s confirmed it as his most famous work. James Travers: “Napoléon is both a stunningly visual work of cinema and a poetically beautiful telling of the life of France’s most famous general.”

Séverin-Mars. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 59. Photo: Film Abel Gance. Publicity still for La Roue/The Wheel (1923).

Gabriel de Gravone. French postcard by Cinémagazine-Edition, no. 224. Photo: G.L. Manuel Frères.

Nicolas Koline as Tristan Fleuri in Napoléon. French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 460. Publicity still for Napoléon (1927).

A Critical And Commercial Disaster

Abel Gance embraced the arrival of sound with enthusiasm and his first production was La Fin du monde/End of the World (1931) starring Victor Francen and Gance himself. This was an expensive science-fiction film about a comet hurling toward Earth on a collision course and the different reactions to people on the impending disaster. Gance had edited it to a running time of just over three hours. When the backers felt that the film was becoming far too long, they took production control away from Gance and cut the film to a shorter length. The result was a critical and commercial disaster. Thereafter the creative independence which Gance had enjoyed in the previous decade was seriously curtailed. He continued to be a busy film-maker throughout the 1930’s, but he characterised most of the films made during this period as ones that he did ‘not in order to live, but in order not to die’. In 1932 he tried to demonstrate his credentials as a reliable and efficient director by filming a remake of Mater dolorosa which he completed within 18 days and within budget. Among the other 'commercial' works that followed were Lucrèce Borgia/Lucretia Borgia (1935) with Edwige Feuillère, and Un Grand Amour de Beethoven/Beethoven's Great Love (1937), with Harry Baur as the composer. One of the more personal projects that he was able to undertake was a new version of J'accuse/I Accuse (1939) starring Victor Francen, not so much a remake of his 1919 film as a continuation of it. Gance conceived it as a warning against the new war that he saw impending. In the upheaval following the German invasion of France in the summer of 1940, Gance went to the Free Zone in the south. He arranged a contract to make a film, Vénus aveugle/Blind Venus (1941) featuring Viviane Romance, at the Victorine studios in Nice. He saw it as an allegory of the current state of France and a message of hope directed to the ordinary French people in their time of misfortune. At this period Gance was among those who saw Philippe Pétain as the means of the country's salvation, and in September 1941 Vénus aveugle had its first screening in Vichy, preceded by a speech in which Gance paid tribute to Pétain. On the other hand, even before its première the film became the object of an attack from the collaborationist and anti-Semitic newspaper Aujourd'hui, which insinuated that the freedoms of film-making in the unoccupied zone in the south of France were being exploited by Jews: the producer Jean-Jacques Mecatti, Viviane Romance, and Gance himself were singled out for derisive references to their Jewish connections. After completing one more film, Le Capitaine Fracasse/Captain Fracasse (1943) with Fernand Gravey, Gance went to Spain in August 1943, citing growing hostility from the German authorities in France. He remained there until October 1945. After the war, his difficulties in getting support for his projects increased and he made few films. The historical melodrama La Tour de Nesle/Tower of Nesle (1954) with Silvana Pampanini and Pierre Brasseur was his first film in colour. It provoked some revival of interest in his work, and François Truffaut named Gance a neglected auteur of genius. Gance returned to Napoleonic spectacle with Austerlitz/The Battle of Austerlitz (1960) starring Pierre Mondy as Napoleon. He made a further historical pageant in Cyrano et d'Artagnan/Cyrano and d'Artagnan (1963) starring José Ferrer and Jean-Pierre Cassel, and then moved into television for his final works, also on historical subjects. Throughout his life, Gance kept returning to Napoléon, often editing his own footage into shorter versions, adding a soundtrack, sometimes filming new material, and as a result the original 1927 film was lost from view for decades. After various attempts at reconstruction, the dedicated work of the film historian Kevin Brownlow produced a five-hour version of the film, still incomplete but fuller than anyone had seen since the 1920’s. This version was presented at the Telluride Film Festival in August 1979, with the frail 89-year old director in attendance. The occasion brought a belated triumph to Gance's career, and subsequent performances and further restoration made his name known to a worldwide audience. Abel Gance married three times: in 1912 to Mathilde Thizeau; in 1922 to Marguerite Danis (sister of Ida); in 1933 to Marie-Odette Vérité (Sylvie Grenade), who died in 1978. Gance died of tuberculosis in Paris in 1981 at the age of 92. He still had plans of making an epic film about Christopher Columbus.

Trailer for Napoleon (1927), presented by San Francisco Silent Film Festival. Source: SFSilent Film (YouTube).

Sources: James Travers (Films de France), Wikipedia, AllMovie and IMDb.

No comments:

Post a Comment